Claim

|

|

Verdict

|

| Prescribed burning damages habitat and wildlife including mosses, birds, invertebrate and reptiles. |

|

The claim is largely unsupported when muirburn is applied under best practice. Evidence shows that poorly managed or uncontrolled fires can harm peat-forming mosses such as Sphagnum and some invertebrates, yet rotational muirburn conducted during wet winter conditions generally avoids heating peat layer, maintains habitat structure, and supports species diversity. Long-term studies indicate that rotational burning can promote a mosaic of vegetation, prevent woody overgrowth, and sustain populations of key birds such as golden plover, curlew, and red grouse. Invertebrate communities appear largely resilient to well-timed burns, and overall biodiversity benefits from maintaining mixed-age vegetation. By comparison, unmanaged vegetation accumulation increases wildfire risk, which causes far greater ecological damage, including widespread destruction of moss layers and nesting habitats.

Therefore, while there is some potential for localised damage if burning is not managed correctly, the weight of scientific evidence supports the view that controlled, rotational burning is compatible with maintaining peatland habitat and wildlife. Claims of broad-scale harm are unsupported and fail to account for the ecological and wildfire mitigation benefits of prescribed burning. |

Where the claim came from

Recent discussions around redefining “deep peat”, lowering the threshold from 40cm to 30cm, will significantly expand the area covered by this definition by up to 168%. This would amount to nearly 1 million acres (around 677,000 hectares) of English moorlands 1. This change could bring more land under restrictions that affect traditional management practices, such as controlled heather burning. This long-used technique for managing upland vegetation, has come under growing scrutiny in recent years due to climate pressures, negative media attention, and fears over greenhouse gas emissions2-4.

Some groups are now calling for a complete ban on all controlled burning on peatland, claiming that the practice damages the habitat and its wildlife including mosses, birds, invertebrates and reptiles5,6. But what does the scientific evidence actually say?

What is muirburn?

Otherwise known as prescribed or controlled burning, this technique has been used for centuries to manage moorland ecosystems. It creates a mosaic of mixed-age vegetation which is preferred by red grouse and other wildlife7,8 It is also used to improve grassland for grazing9.

Otherwise known as prescribed or controlled burning, this technique has been used for centuries to manage moorland ecosystems. It creates a mosaic of mixed-age vegetation which is preferred by red grouse and other wildlife7,8 It is also used to improve grassland for grazing9.

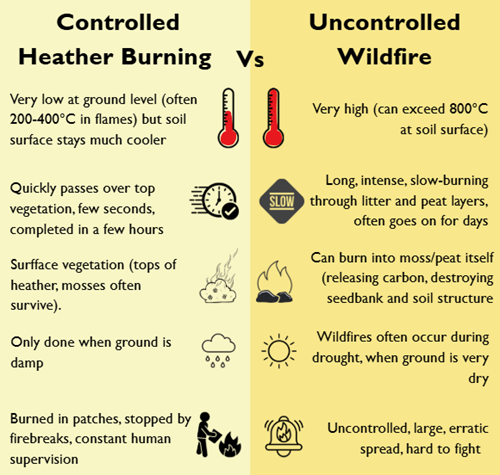

Muirburn is a fast-moving surface fire, primarily targeting the tops of surface vegetation. Ground temperatures during these burns stay low, and anecdotally are not even hot enough to melt a chocolate bar placed on the soil10. Multiple peer-reviewed studies reinforce this and new research from Exeter University confirms the distinction between controlled burns and wildfires, in terms of intensity and soil heat exposure11.

Photo credit: Laurie Campbell

What is wildfire?

Despite common confusion, controlled burns fundamentally differ from wildfires. A wildfire is an unplanned, uncontrolled fire that spreads through vegetation such as forests, grasslands, shrublands or peatlands. Wildfire are typically driven by factors such as weather and fuel load and can be ignited by accidental ignitions such as campfires, sparks from infrastructure or deliberate burns that escape control in dry conditions3,12,13.

In contrast to muirburn, wildfires smoulder deep into the organic soils in peatlands14–16. The subsequent ecological damage depends on the fire intensity, severity and frequency17,18.

In contrast to muirburn, wildfires smoulder deep into the organic soils in peatlands14–16. The subsequent ecological damage depends on the fire intensity, severity and frequency17,18.

What is fuel load?

Fuel load is the amount of combustible material i.e. both living and dead vegetation, leaf litter, shrubs etc. that is available to catch fire in an area. It is a key factor influencing how intensely a fire burns, how quickly it spreads and how difficult it is to control.19

Taller, denser vegetation like heather tends to burn hotter and for longer than younger, dwarf shrubs20. A 2014 study found fuels, like heather, charred at higher temperatures (~646°C) compared to ground fuels like roots and peat soil (~447°C) during fires on peatland 21. This suggests that surface vegetation can be managed to minimize peat damage.

This is often referenced as an additional benefit of prescribed burning. Reducing this fuel load in a controlled manner helps to prevent large, intense wildfires, which are increasingly recognised as a major threat to peatland systems22. However, there are concerns that muirburn could damage the peat layer, which is essential for biodiversity and carbon storage5,23.

The table below compares key features of controlled burns and wildfires:

Effects on vegetation

The impact of controlled burning on upland ecosystems is widely debated, with both potential benefits and risks reported. Although burning is now restricted on deep peat within designated sites and discontinued across many conservation-managed moors, claims that the practice offers ‘no ecological value’ are misleading24. Many studies show that when carefully applied and guided by best practice, controlled burning can deliver positive outcomes for wildlife8,25,26. Meanwhile, there has been no formal review to see if the current restrictions have benefited the landscapes ecology in practice.

Furthermore, controlled burning helps to maintain a mix of vegetation, including heather, cotton grass and sphagnum moss in its favourable state for crucially threatened species such as curlew and golden plover. It prevents tall, woody overgrowth from choking slower-growing mosses, which are vital for peat formation and carbon capture, supporting both biodiversity and climate goals 27,28.

Importantly, heather moorland itself is an internationally rare habitat, recognised for its ecological value under the 1992 Rio Convention on Biodiversity. While some argue that heather dominance should be reduced, it is crucial to acknowledge that managing heather is not about eliminating it, but about maintaining the right balance of species, including mosses and grasses, to support a wider ecological network.

Long-term research in the North Pennines has shown that a 10-year burning cycle can benefit peat-forming species like Sphagnum mosses and cotton grass. In contrast, sites burned at longer intervals (20+ years) see increased heather cover and declines in bog species27. Some studies present this as a negative outcome, suggesting that encouraging grasses at the expense of other species can make the ecosystem unfavourable29-31. According to these papers the suggested 10 year burning cycle is insufficient to allow full recovery of the bog species back to its pre-burn state31,32.

Poorly managed burns can reduce sphagnum moss, a key peat-forming species33–36. However, aerial imagery and field surveys reveal that sphagnum and cotton grass are most abundant in areas burned 3–10 years ago, while older burns show less27. Further research published in 2021 found that Sphagnum cover was five times higher in 8–10 year-old burns, compared to unburned sites25,37. These findings suggest that when conducted responsibly and at the right intervals, prescribed burning may support peatland restoration by reducing heather dominance and promoting peat-forming species.

Peatland management should reflect its objectives, and cannot be seen as a homogenous approach when the aim should be biodiversity. While some argue against reducing heather, managing its growth is crucial. A diverse vegetation structure, which balances heather, moss and grasses, better supports bird populations and helps maintain low wildfire risk. The question is whether to let vegetation overgrow before intervention or manage it continuously to preserve ecological balance29.

Effects on wildlife

There is little direct evidence that well-executed muirburn harms wild animals. In contrast, a build-up of unmanaged vegetation significantly raises the risk of severe wildfires, which are far more destructive8,12,38. There are conflicting reports on if there is any significant short-term loss of insect communities in the areas where vegetation has been burnt5,36. However across Scotland and northern England there are plenty of reports that the bird life which inevitably feeds on these insects use the burned areas to nest 8,37,38.

Many studies show that densities of breeding European golden plover, ring ouzel, northern lapwing, red grouse, and Eurasian curlew are higher on grouse moors managed with rotational burning compared to unmanaged moors8,38,39. Higher-than-average populations of hares and several species of raptors are also reported7,40.

In contrast, areas where muirburn has largely stopped, such as parts of Wales, often fail to reverse bird declines. This highlights the consequences of losing grouse moor management, including habitat and predator control. The country’s heather habitat has declined by an estimated 46%. A study in North Berwyn (1983–2002) recorded breeding declines in lapwing (disappeared entirely), golden plover (- 90%), curlew (-79%), ring ouzel (-80%), black grouse (-78%), and red grouse (-54%). This is all while carrion crow numbers rose by 526%, furthering the predation pressure on the nests of these threatened birds41.

Around £1 million in private investment is spent annually on moorland management for red grouse, contributing over 30,000 ha of peatland restoration - over a quarter of the UK Government's 2025 peatland restoration target in recent years4243. Matching this through public funding alone would be difficult, highlighting the importance of collaboration with moorland managers.

Contrary to claims that muirburn causes wildfires, research shows that 96% of wildfire-affected areas lie outside muirburn managed moorlands. Wildfires are more common in unmanaged heather, grasslands, and peat soils, where fuel accumulates22. Where burning is removed, vegetation becomes overgrown, increasing bracken and birch scrub, which increases wildfire risk12,37.

Common questions

Do controlled burns make peat hydrophobic?

Concerns that fire might cause peat soils to become water-repellent (hydrophobic) is often raised 23,31. . Wildfires are known to create hydrophobic conditions in peat soils. This effect is linked to the higher temperatures and longer burn times of wildfires. Studies consistently show stronger water repellency under more severe fire conditions. This can disrupt peatland water balance and increase evaporation rates13,44. The evidence that prescribed burns cause hydrophobicity is far weaker.

Natural England’s NEER155 review found only weak evidence that controlled burning increases peat surface hydrophobicity. One of the studies in the review did not measure hydrophobicity directly. Instead, it inferred the effect from moss species linked to dry or water-repellent conditions. In practice, the results showed that moss was unlikely to become water-repellent, especially in wet conditions such as those after muirburn45. More recent studies even suggest that may have the opposite in boreal peatlands, making soils more easily wetted rather than resistant to water46. Even so, more long-term research is needed to understand impacts across difference sites.

How does moisture/water levels affect burning?

Peat moisture is key to its fire resilience as it insulates against heat penetration47. Wet, intact peatlands are more resistant to damage from heat, while dry, degraded peat is more vulnerable21,48. Crucially, muirburn usually occurs during late winter when soils are wet, providing some natural protection to the peat/moss layer26. Controlled burns carried out during these wet conditions are far less damaging than wildfires in dry summers. When done properly, they avoid heating the soil or harming peat layers as wildfires do.

What impact does draining have on burning?

In contrast, drained peatlands, where water tables are artificially lowered, are generally more fire-prone and less favourable for sphagnum moss, increasing ignition risk and fire severity 21,49. Some studies critiquing prescribed burning may not adequately separate the effects of fire from prior drainage, as the two often occur together, complicating interpretations of fire-related damage. Furthermore, many quoted studies raising concerns around damage caused by controlled burns, are based on management occurring prior to increased regulations and best practice guidelines set between 2001-2007. Many evidence reviews continue to build on this outdated literature rather than critically analysing its current relevance during updates.

Do rotation schedules matter?

As part of muirburn best practice, burns are usually applied in rotations, to stimulate shoot and moss regrowth and preserve habitat structure26,27. This does not occur in fixed cycles, but is based on local site conditions and vegetation growth rates. For example, on some wetter bogs, burning may not be needed for 25-30 years.

While one 2005 study hypothesised that regular burning could degrade peat bog microtopography and increase wildfire risk49 , the evidence for this remains limited and site specific. Recent work, such as Heinmeyer’s long-term study on blanket bogs, suggests that unmanaged heather can lead to lower water tables, increasing fire risk50,51. In contrast, low-intensity, rotational burns, can help reduce wildfire fuel-load and the woody vegetation which draws water from the soil, further drying out the peat50. As a result, controlled burning may lower both the frequency and intensity of wildfires22,51,52.

The role of cutting

Controlled burning does not need to be the sole method for managing the UK’s peatlands. A range of techniques, including rewetting, cutting, and grazing, can coexist as part of a spectrum of land management practices rather than being viewed as mutually exclusive.

Historically, heather burning helped protect moorlands from damaging practices like drainage or afforestation. From the 1940s–80s, moors where grouse shooting stopped lost 41% of heather cover, compared to 24% where it continued8. Where burning has stopped, overgrown heather has been reported to suppress sphagnum and dry out peat soils37. This highlights that heather must be managed in some form to maintain the ecological integrity of these habitats.

Cutting is increasingly used, especially on blanket bogs, but remains under-researched on deep peat. Natural England’s NEER028 review found limited and inconclusive evidence on the long-term effects of cutting, particularly in comparison to burning53. However, the evidence base for this is currently too weak to support large-scale shifts in policy in favour of cutting alone.

While there is some evidence it improves heathland structure and supports invertebrates like carabid beetles and spiders54, heavy cutting machinery can damage moss layers, impact the micro-topography (hummock and pool characteristics) and compact peat55,56. Research shows that cutting can flatten these features, reduce water retention, and impair the growth of mosses like sphagnum. In Upper Teesdale, cutting reduced vegetation height by 62% and moss depth by nearly 40%, with some areas scalped or moss completely removed57. The role of cutting in wildfire mitigation is dependent upon the removal of the brash26,58. This damage can be long-lasting, and may undermine the very restoration goals that cutting seeks to achieve56.

Cutting can reduce surface fuel loads and may help mitigate wildfire risk, but only if the cut material (brash) is removed. If left in place, this brash can dry and accumulate, creating a dense, combustible layer that may increase fire severity. While specific UK references on this remain limited, studies in similar ecosystems support this concern59. Greater field-based evidence is needed to assess how brash removal affects wildfire mitigation in UK uplands.

Cutting can help remove nitrogen by taking away biomass, but similar results are possible through carefully timed burning and light-touch grazing60,61. Neither method removes enough biomass alone to prevent long-term buildup. A mixed approach- combining low-intensity muirburn with targeted cutting may be more effective—especially as burning emits less phosphorus than cutting62.

Mowing may also flatten natural bog topography and reduce resilience to droughts. However decadal mowing cycles can support heather regeneration and reduce soil carbon loss under drought stress 63. Heinemeyer found that over 10 years, burning may emit no more carbon than cutting due to charcoal formation. He also warns that rewilding can increase vegetation density, drying out peat and raising wildfire risk64.

The role of rewetting

Rewetting is a valuable tool for reversing historical damage from moorland drainage, raising the water table via dams which slow water loss and restore peatland hydrology 65. Wetter soils reduce fire risk and support peat-forming mosses like Sphagnum66. A 2024 study found that rewetting significantly reduces CO₂ emissions over time, though it may lead to increased methane (CH₄) emissions due to anaerobic condition – a common trade-off in wetland restoration24,67

However, rewetting is not without its challenges, particularly under climate change. Studies have shown that climate change may alter seasonal water table dynamics, potentially limiting the effectiveness of rewetting, especially in summer68. Other work also noted that summary water table drawdown can persist despite restoration efforts, particularly during drought years62,67.

Rewetting can mobilise nutrients such as phosphorus that were previously locked in dry peat soil, this could have knock on effects for water quality 69. If overdone, rewetting can lead to "helophytisation"—a shift toward tall wetland plants like reeds (Phragmites australis) and cattails (Typha latifolia) that outcompete mosses and lower biodiversity70,71.

Another concern is the methods interaction with grazing72. While some fear rewetting reduces land suitability, a 2011 study found sheep preferred wetter areas9. However, grazing reductions, whether due to policy or wetter conditions, have also been linked to increased vegetation overgrowth and tick burdens, which in turn can harm ground nesting birds 73,74. In the past, light grazing helped manage tick populations and maintain vegetation structure. Therefore, supporting an appropriate level of grazing, in tandem with rewetting and controlled burns may be key to supporting both livestock and biodiversity goals. 10,71–74.

Conclusions

Rather than focusing narrowly on limiting prescribed burning, effective peatland policy should promote an ecologically driven mix of interventions, including burning, cutting, grazing, and rewetting, tailored to the specific needs of each landscape. Grouse moor managers, with their deep local knowledge, already play a vital role in wildfire response and land stewardship. Supporting them is essential to ensuring sustainable outcomes for both climate and biodiversity.

Rather than focusing narrowly on limiting prescribed burning, effective peatland policy should promote an ecologically driven mix of interventions, including burning, cutting, grazing, and rewetting, tailored to the specific needs of each landscape. Grouse moor managers, with their deep local knowledge, already play a vital role in wildfire response and land stewardship. Supporting them is essential to ensuring sustainable outcomes for both climate and biodiversity.

Blanket approaches are unlikely to succeed. Instead, site-sensitive, adaptive management, built on evolving evidence, is needed to restore and protect the UK’s peatlands. Wildfire education and active prevention must also be prioritised, especially in unmanaged areas where fire risks are rising. Removing traditional land management without appropriate alternatives only accelerates the decline of biodiversity and ecosystem health. A collaborative approach, recognising land managers as key partners, is the most effective path forward.

References

- n.d. Defra consulting on proposals to further restrict heather burning - Shooting UK.

- Matt Davies, G, Kettridge, N, Stoof, CR, et al., 2016. The peatland vegetation burning debate: Keep scientific critique in perspective. a response to brown et al. and douglas et al. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 371:.

- Davies, GM, and Legg, CJ, 2016. Regional variation in fire weather controls the reported occurrence of Scottish wildfires. PeerJ. 2016: e2649.

- Davies, GM, Kettridge, N, Stoof, CR, et al., 2016. The role of fire in UK peatland and moorland management: the need for informed, unbiased debate. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 371:.

- n.d. EMBER EFFECTS OF MOORLAND BURNING ON THE ECOHYDROLOGY OF RIVER BASINS EMBER PROJECT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.

- n.d. Burning & Peatlands | IUCN UK Peatland Programme.

- Hesford, N, Fletcher, K, Howarth, D, et al., 2019. Spatial and temporal variation in mountain hare (Lepus timidus) abundance in relation to red grouse (Lagopus lagopus scotica) management in Scotland. European Journal of Wildlife Research. 65:.

- Tharme, AP, Green, RE, Baines, D, et al., 2001. The effect of management for red grouse shooting on the population density of breeding birds on heather-dominated moorland. Journal of Applied Ecology. 38: 439–457.

- Wilson, L, Wilson, JM, and Johnstone, I, 2011. The effect of blanket bog drainage on habitat condition and on sheep grazing, evidence from a Welsh upland bog. Biological Conservation. 144: 193–201.

- n.d. A COLLECTION OF CASE STUDIES IN THE WORKING CONSERVATIONIST SERIES Real Wilders How grouse management compares with alternative land uses in delivering for climate and wildlife A HAVEN FOR RARE BIRDS IN COUNTY DURHAM THE IMPACT OF AFFORESTATION IN GALLOWAY FIGHTING FIRE WITH FIRE IN THE PEAK DISTRICT WHY THE BERWYN HILLS FELL SILENT CAIRNGORMS CAPERCAILLIE CONSERVATION INSIDE.

- Matt Davies, G, Adam Smith, A, MacDonald, AJ, et al., 2010. Fire intensity, fire severity and ecosystem response in heathlands: factors affecting the regeneration of Calluna vulgaris. Journal of Applied Ecology. 47: 356–365.

- Reid, N, Kelly, R, and Montgomery, WI, 2023. Impact of wildfires on ecosystems and bird communities on designated areas of blanket bog and heath. Bird Study. 70: 113–126.

- Davies, GM, Domènech, R, Gray, A, et al., 2016. Vegetation structure and fire weather influence variation in burn severity and fuel consumption during peatland wildfires. Biogeosciences. 13: 389–398.

- Rein, G, Cohen, S, and Simeoni, A, 2009. Carbon emissions from smouldering peat in shallow and strong fronts. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute. 32: 2489–2496.

- Rein, G, Cleaver, N, Ashton, C, et al., 2008. The severity of smouldering peat fires and damage to the forest soil. CATENA. 74: 304–309.

- Hadden, RM, Rein, G, and Belcher, CM, 2013. Study of the competing chemical reactions in the initiation and spread of smouldering combustion in peat. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute. 34: 2547–2553.

- Matt Davies, G, Adam Smith, A, MacDonald, AJ, et al., 2010. Fire intensity, fire severity and ecosystem response in heathlands: Factors affecting the regeneration of Calluna vulgaris. Journal of Applied Ecology. 47: 356–365.

- Malone, S, and O’Connell, C, 2009. Ireland’s Peatland Conservation Action Plan 2020–Halting the Loss of Peatland Biodiversity. Kildare: Irish Peatland Conservation Council.

- n.d. Prescribed Fire Basics: Fuels | OSU Extension Service.

- Davies, GM, Legg, CJ, Smith, AA, et al., 2009. Rate of spread of fires in Calluna vulgaris-dominated moorlands. Journal of Applied Ecology. 46: 1054–1063.

- Hudspith, VA, Belcher, CM, and Yearsley, JM, 2014. Charring temperatures are driven by the fuel types burned in a peatland wildfire. Frontiers in Plant Science. 5: 116852.

- Fielding, D, Newey, S, Pakeman, RJ, et al., 2024. Limited spatial co-occurrence of wildfire and prescribed burning on moorlands in Scotland. Biological Conservation. 296: 110700.

- Clay, GD, Worrall, F, and Aebischer, NJ, 2012. Does prescribed burning on peat soils influence DOC concentrations in soil and runoff waters? Results from a 10 year chronosequence. Journal of Hydrology. 448–449: 139–148.

- Ashby, MA, and Heinemeyer, A, 2021. A Critical Review of the IUCN UK Peatland Programme’s “Burning and Peatlands” Position Statement. Wetlands. 41: 1–22.

- n.d. Managed burning can benefit peatland, new study suggests - Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust.

- n.d. Guidance - The Muirburn Code | NatureScot.

- Whitehead, SC, and Baines, D, 2018. Moorland vegetation responses following prescribed burning on blanket peat. International Journal of Wildland Fire. 27: 658–664.

- n.d. Heather burning - Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust.

- Stewart, GB, Coles, CF, and Pullin, AS, 2005. Applying evidence-based practice in conservation management: Lessons from the first systematic review and dissemination projects. Biological Conservation. 126: 270–278.

- Ward, SE, Bardgett, RD, McNamara, NP, et al., 2007. Long-term consequences of grazing and burning on northern peatland carbon dynamics. Ecosystems. 10: 1069–1083.

- Ramchunder, SJ, Brown, LE, and Holden, J, 2009. Environmental effects of drainage, drain-blocking and prescribed vegetation burning in UK upland peatlands. Progress in Physical Geography. 33: 49–79.

- Hobbs, RJ, 1984. Length of burning rotation and community composition in high-level Calluna-Eriophorum bog in N England. Vegetatio. 57: 129–136.

- Lee, H, Alday, JG, Rose, RJ, et al., 2013. Long-term effects of rotational prescribed burning and low-intensity sheep grazing on blanket-bog plant communities. Journal of Applied Ecology. 50: 625–635.

- Noble, A, Palmer, SM, Glaves, DJ, et al., 2019. Peatland vegetation change and establishment of re-introduced Sphagnum moss after prescribed burning. Biodiversity and Conservation. 28: 939–952.

- Smith, SM, TAS, & RTRM, 2020. The effects of prescribed burning on blanket bog ecosystems. . Biological Conservation. 246: 108559.

- n.d. An evidence review update on the effects of managed burning on upland peatland biodiversity, carbon and water - NEER155.

- Whitehead, S, Weald, H, and Baines, D, 2021. Post-burning responses by vegetation on blanket bog peatland sites on a Scottish grouse moor. Ecological Indicators. 123:.

- Douglas, DJT, Beresford, A, Selvidge, J, et al., 2017. Changes in upland bird abundances show associations with moorland management. Bird Study. 64: 242–254.

- Fletcher, K, Aebischer, NJ, Baines, D, et al., 2010. Changes in breeding success and abundance of ground-nesting moorland birds in relation to the experimental deployment of legal predator control. Journal of Applied Ecology. 47: 263–272.

- Ludwig, SC, Roos, S, Rollie, CJ, et al., 2020. Long-term changes in the abundance and breeding success of raptors and ravens in periods of varying management of a scottish grouse moor. Avian Conservation and Ecology. 15: 1.

- Warren, P, and Baines, D, 2014. Changes in the abundance and distribution of upland breeding birds in the Berwyn Special Protection Area, North Wales 1983-2002. Birds in Wales. 11: 32–42.

- 2021. England Peat Action Plan.

- n.d. The People’s Plan For The Uplands Information for policymakers on looking after moorland areas and the communities that depend on them regionalmoorlandgroups.com PHOTO BY RMBAILEYMEDIA.

- Kettridge, N, Humphrey, RE, Smith, JE, et al., 2014. Burned and unburned peat water repellency: Implications for peatland evaporation following wildfire. Journal of Hydrology. 513: 335–341.

- Moore, PA, Lukenbach, MC, Kettridge, N, et al., 2017. Peatland water repellency: Importance of soil water content, moss species, and burn severity. Journal of Hydrology. 554: 656–665.

- Wu, Y, Zhang, N, Slater, G, et al., 2020. Hydrophobicity of peat soils: Characterization of organic compound changes associated with heat-induced water repellency. Science of the Total Environment. 714:.

- Matt Davies, G, Adam Smith, A, MacDonald, AJ, et al., 2010. Fire intensity, fire severity and ecosystem response in heathlands: factors affecting the regeneration of Calluna vulgaris. Journal of Applied Ecology. 47: 356–365.

- n.d. Unusual Stands of Birch on Bogs on JSTOR.

- Fernandez, F, Fanning, VM, Mccorry, M, et al., 2005. RAISED BOG MONITORING PROJECT 2004-2005 DOCUMENT 2 SUMMARY TABLES A REPORT TO THE NATIONAL PARKS AND WILDLIFE SERVICE, DUBLIN.

- Heinemeyer, A, 2023. Restoration of heather-dominated blanket bog vegetation for biodiversity, carbon storage, greenhouse gas emissions and water regulation: comparing burning to alternative mowing and uncut management:Final 10-year Report to the Project Advisory Group of Peatland-ES-UK.

- Heinemeyer, A, Ashby, M, Liu, B, et al., 2024. Prescribed heather burning on peatlands: A review of ten key claims made about heather management impacts and implications for future UK policy. Mires and Peat.

- Smith, BM, Carpenter, D, Holland, J, et al., 2023. Resolving a heated debate: The utility of prescribed burning as a management tool for biodiversity on lowland heath. Journal of Applied Ecology. 60: 2040–2051.

- Moody, CS, and Holden, J, 2023. NEER028 Edition 1 The Impacts of Vegetation Cutting on Peatlands and Heathlands - NEER028.

- Pedley, SM, Franco, AMA, Pankhurst, T, et al., 2013. Physical disturbance enhances ecological networks for heathland biota: A multiple taxa experiment. Biological Conservation. 160: 173–182.

- Marrs, RH, Marsland, EL, Lingard, R, et al., 2019. Experimental evidence for sustained carbon sequestration in fire-managed, peat moorlands. Nature Geoscience. 12: 108–112.

- Heinemeyer, A, Berry, R, and Sloan, TJ, 2019. Assessing soil compaction and micro-topography impacts of alternative heather cutting as compared to burning as part of grouse moor management on blanket bog. PeerJ. 2019: e7298.

- Holmes, K, and Whitehead, S, 2022. Immediate Effects of Heather Cutting Over Blanket Bog on Depth and Microtopography of the Moss Layer. Mires and Peat. 28: 25.

- Evans, A, Auerbach, S, Miller, LW, et al., 2015. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Wildfire Mitigation Activities in the Wildland-Urban Interface.

- n.d. Ecological foundations for fire management in North American forest and shrubland ecosystems by J.E. Keeley | Open Library.

- Fagúndez, J, 2013. Heathlands confronting global change: drivers of biodiversity loss from past to future scenarios. Annals of Botany. 111: 151–172.

- Power, SA, Barker, CG, Allchin, EA, et al., 2001. Habitat management: a tool to modify ecosystem impacts of nitrogen deposition? TheScientificWorldJournal. 1 Suppl 2: 714–721.

- Härdtle, W, Niemeyer, M, Niemeyer, T, et al., 2006. Can management compensate for atmospheric nutrient deposition in heathland ecosystems? Journal of Applied Ecology. 43: 759–769.

- Gliesch, M, Sanchez, LH, Jongepier, E, et al., 2024. Heathland management affects soil response to drought. Journal of Applied Ecology. 61: 1372–1384.

- Heinemeyer, and Andreas, 2023. Restoration of heather-dominated blanket bog vegetation for biodiversity, carbon storage, greenhouse gas emissions and water regulation: comparing burning to alternative mowing and uncut management: Final 10-year Report to the Project Advisory Group of Peatland-ES-UK.

- Karimi, S, Maher Hasselquist, E, Salimi, S, et al., 2024. Rewetting impact on the hydrological function of a drained peatland in the boreal landscape. Journal of Hydrology. 641: 131729.

- n.d. Wildfire resilience: why rewetting peatlands must play a key role.

- Balode, L, Bumbiere, K, Sosars, V, et al., 2024. Pros and Cons of Strategies to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Peatlands: Review of Possibilities. Applied Sciences 2024, Vol. 14, Page 2260. 14: 2260.

- Ritson, JP, Lees, KJ, Hill, J, et al., 2025. Climate change impacts on blanket peatland in Great Britain. Journal of Applied Ecology. 62: 701–714.

- n.d. Questions & Answers: Bringing Clarity on Peatland Rewetting and Restoration.

- Kreyling, J, Tanneberger, F, Jansen, F, et al., 2021. Rewetting does not return drained fen peatlands to their old selves. Nature Communications. 12: 1–8.

- Loisel, J, and Gallego-Sala, A, 2022. Ecological resilience of restored peatlands to climate change. Communications Earth and Environment. 3: 1–8.

- Wichmann, S, and Nordt, A, 2024. Unlocking the potential of peatlands and paludiculture to achieve Germany’s climate targets: obstacles and major fields of action. Frontiers in Climate. 6: 1380625.

- n.d. Sheep decline “raises tick risk” says NFUS - BBC News.

- n.d. Disease control on grouse moors - Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust.